Remembering Jonathan Daniels

Originally published in The Laconia Daily Sun ›

Last Sunday, the day before we celebrated and remembered the work and legacy of Martin Luther King, I attended the Adult Forum lecture at Grace Church where Dr. Nicholas Birns discussed an article entitled “Nonviolence and Racial Justice” published by Dr. King in Christian Century a liberal religious magazine, 6 February 1957.

Then I traveled uptown by subway to the Sugar Hill Children’s Museum of Art and Storytelling on 155th Street and St. Nicholas Avenue to participate in their programs and events for families, adults and children, around the legacy of Dr. King. This neighborhood is called “Sugar Hill” because in the 1920s it was home for many of the well-known African Americans including W.E. B. DuBois, Thurgood Marshall, Adam Clayton Powell, Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway and Arturo Schomburg, among others, who were living there.

On Tuesday evening I was in conversation with Gabrielle Bellot and Nicholas Boggs at the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine where I am the Madeleine L’Engle Fellow. Our “Close Conversation” was entitled, “Interpreting James Baldwin Today.” We discussed Baldwin’s novel, If Beale Street Could Talk (Dial Press, 1974) recently released as a movie directed by Barry Jenkins, and Little Man, Little Man (Dial Press, 1976) Baldwin’s only children’s book with illustrations by Yoran Cazac. Little Man was recently republished under the direction of Nicholas Boggs and Jennifer DeVere Brody

Through my reading and research, I kept thinking about Jonathan Daniels.

Jonathan Myrick Daniels was born in Keene, New Hampshire on 20 March 1939, the son of Dr. and Mrs. Philip Brock Daniels. “Jon” as he was known to friends, wasn’t certain about what he wanted to do when he was growing up, although he thought about the ministry. After graduating from high school, he attended Virginia Military Institute, a decision that surprised his classmates. Then, after graduating from VMI he attended Harvard University to study English literature. Leaving Harvard, he returned to Keene to help his family after his father’s death, holding a job at an “electrical concern” in Keene and at Elliott Community Hospital.

In September 1963 he returned to Cambridge, Massachusetts and entered the Episcopal Theological School. Two years later in March 1965 he decided to travel to Selma, Alabama and support the work of Dr. Martin Luther King who had issued a plea within the faith community for help in the civil rights movement.

On August 20, 1965 Jon was shot to death in broad daylight by a white policeman, who had been intending to shoot a 16-year-old black girl. Jon Daniels pushed the girl aside so her life would be saved and died in the process. The deputy sheriff was acquitted.

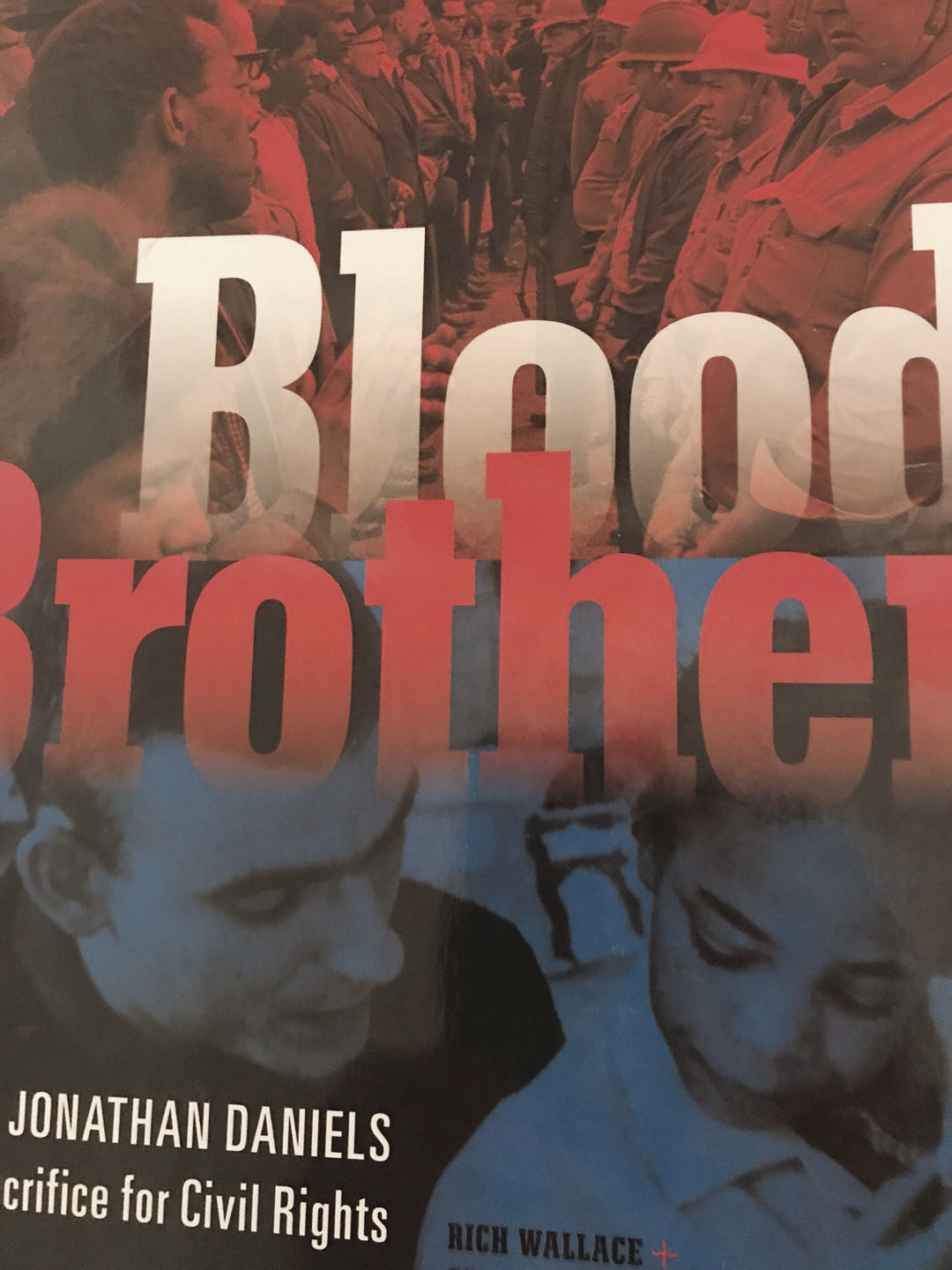

The incident has been written about in American Martyr, The Jon Daniels Story by William J. Schneider (Morehouse Publishing, 1972) and in Blood Brothers, Jonathan Daniels and His Sacrifice for Civil Rights by Rich Wallace and Sandra Neil Wallace (Calkins Creek 2016).

A Center for Justice has been established in Jonathan’s memory in Keene and one can visit the Jonathan Daniels Elementary School, the Jonathan Daniels Trail Ashuelot River Park and the shrine inside the St. James Episcopal Church sanctuary in Keene.

James Baldwin wrote Little Man, Little Man from the perspective of a child growing up in Harlem. He wrote in Black English, which he explained in an essay entitled, “If Black English Isn’t a Language, Then Tell Me, what is?” How different James Baldwin’s life was growing up in Harlem from Jonathan Daniel’s life growing up in New Hampshire. How different all of our lives are. One from another.

Mohandas K. Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Nelson Mandela … in the words of Dr. King: “…nonviolent resistance does not seek to defeat or humiliate the opponent, but to win his friendship and understanding.”